- Investor Briefcase

- Posts

- The genius hedge fund that fell apart overnight

The genius hedge fund that fell apart overnight

How LTCM's collapse nearly triggered a global financial crisis

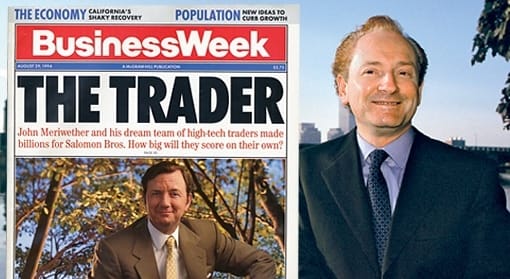

John Meriwether built one of Wall Street’s most legendary trading desks at Salomon Brothers before launching Long-Term Capital Management along with two Nobel Prize-winning economists. Within three years, the fund was compounding capital at over 40 percent a year with minimal volatility. LTCM became the most prestigious hedge fund in the world, until it all collapsed.

This week, we break down how LTCM, once considered an indestructible genius hedge fund, nearly triggered a global financial crisis, and the aftermath:

🧠 The genius hedge fund

🏛️ The collapse that shook Wall Street

📉 Aftermath and the limits of genius

— Investor Briefcase Team

In the early 1990s, John Meriwether was already famous for building Salomon’s powerhouse arbitrage group. When he left to start his own firm, investors paid attention. He recruited a dream team of traders, academics, and economists. The most famous names were Nobel laureates Myron Scholes and Robert C. Merton, two professors who helped formalize modern options pricing theory. Together, they formed Long-Term Capital Management in 1994.

The strategy was based on quantitative arbitrage. The firm used complex models to identify price inefficiencies across global markets. These inefficiencies were often tiny, but with enough leverage and diversification, they could produce consistent gains. LTCM was methodical, math-driven, and confident. In the first few years, the returns were spectacular.

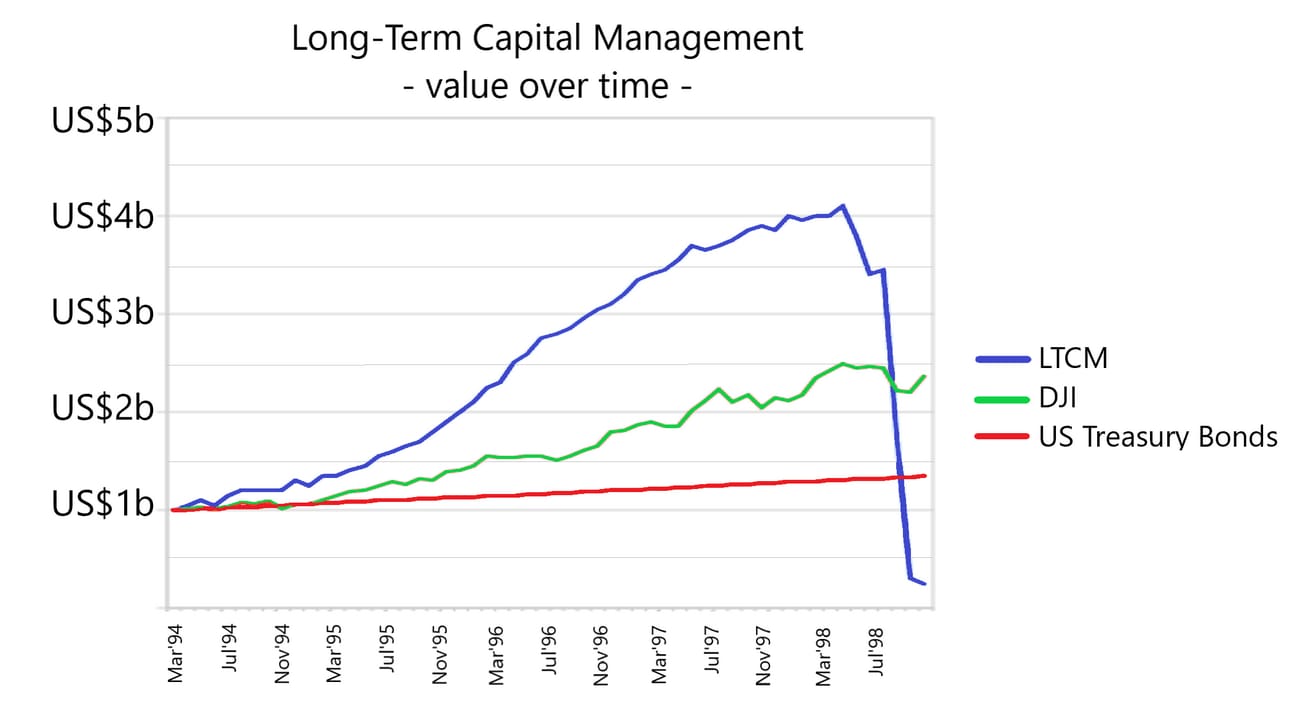

The fund returned 21 percent in 1995, 43 percent in 1996, and followed up with 41 percent in 1997, drawing in a flood of institutional capital. At its peak, LTCM had nearly $5 billion in capital under management and over $125 billion in assets underpinned by borrowed funds. Its balance sheet rivaled that of major investment banks.

“They thought they were perfectly hedged. It’s hard to imagine anyone thinking that now.”

The firm had positions across global bond markets, equities, and derivatives. The scale and confidence of its trades created a perception that LTCM had unlocked a new way of managing risk. That perception, as it turned out, was a critical part of the problem.

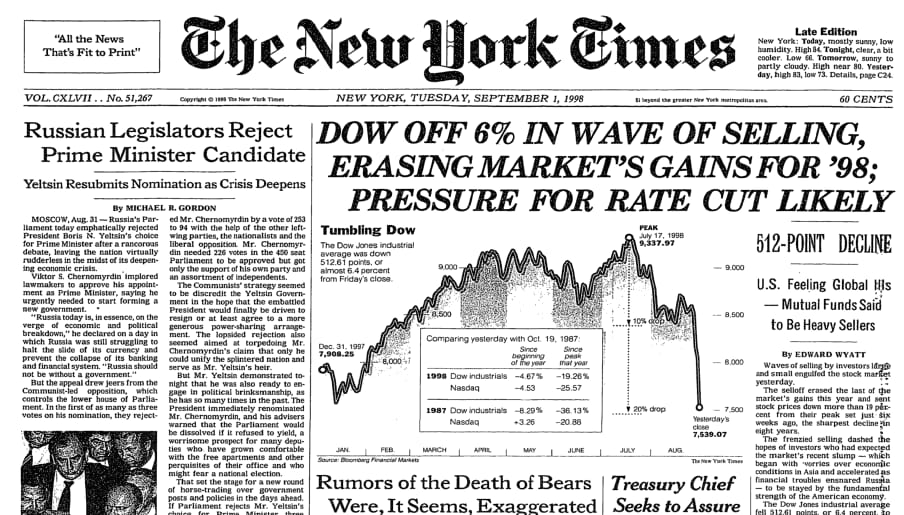

The New York Times front page after Russia defaulted

In August 1998, Russia defaulted on its sovereign debt. Global markets reacted violently. Investors rushed to sell risk and buy safe assets. Treasury bonds surged, credit spreads widened, and prices moved in ways that contradicted LTCM’s expectations.

The models had not anticipated such a scenario. The fund had been highly leveraged, with over 25 dollars of exposure for every dollar of capital. Small moves in the wrong direction quickly became existential threats. The fund lost $550 million in a single day and in just four months, lost $4.6 billion.

LTCM had trades across every major financial institution. If the fund collapsed, it risked triggering a cascade of failures across the system. The Federal Reserve intervened to coordinate a private rescue. Fourteen of the largest Wall Street firms, including Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, and JPMorgan, contributed a combined $3.6 billion to stabilize the fund and unwind its positions in an orderly way.

“It was the closest thing to a true financial meltdown since the Great Depression.”

By the end of 1998, LTCM had been effectively dismantled. The investors were wiped out, the founders were removed, and the firm ceased operations shortly after.

Sponsored by Pacaso

He’s already IPO’d once – this time’s different

Spencer Rascoff grew Zillow from seed to IPO. But everyday investors couldn’t join until then, missing early gains. So he did things differently with Pacaso. They’ve made $110M+ in gross profits disrupting a $1.3T market. And after reserving the Nasdaq ticker PCSO, you can join for $2.80/share until 5/29.

This is a paid advertisement for Pacaso’s Regulation A offering. Please read the offering circular at invest.pacaso.com. Reserving a ticker symbol is not a guarantee that the company will go public. Listing on the NASDAQ is subject to approvals. Under Regulation A+, a company has the ability to change its share price by up to 20%, without requalifying the offering with the SEC.

The collapse of LTCM forced the industry to rethink how it approached risk. The fund had world-class talent, sophisticated models, and access to the best data available. Yet it still failed because it ignored uncertainty, treated rare events as negligible, and relied heavily on leverage.

John Meriwether later launched JWM Partners, a second fund that eventually shut down during the 2008 crisis. Merton and Scholes returned to academia and continued to advise financial institutions. Their reputations were complicated by LTCM, but their academic work remained foundational to modern finance.

The lessons from LTCM resurfaced during the 2008 financial crisis with many of the same problems appearing again. Complex models, large exposures, and overconfidence in historical data contributed to another near-collapse. This time, the consequences were even more widespread.

“The markets can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.”

For students drawn to quant roles or elite firms, the story of LTCM is essential reading. Intelligence matters, but humility and risk control matter more. The difference between being right in theory and surviving in practice often comes down to how well you prepare for the events your models fail to predict.

More Stories

Other major financial collapses

> Lehman Brothers (2008): Once the fourth-largest U.S. investment bank, Lehman collapsed under $600B in assets due to massive exposure to subprime mortgages. Its bankruptcy triggered the global financial crisis and reshaped Wall Street regulation.

> Archegos Capital (2021): Family office of Bill Hwang used extreme leverage through swaps to build massive positions. A sudden margin call erased $20B and caused multi-billion losses at global banks.

> Amaranth Advisors (2006): A $9B hedge fund wiped out in a week after trader Brian Hunter lost $6B betting on natural gas. Its collapse exposed the dangers of concentrated positions and weak risk controls.

> Barings Bank (1995): Britain’s oldest bank collapsed after rogue trader Nick Leeson racked up £827M in losses on unauthorized derivatives trades, exposing major failures in oversight.

Each week we profile the most notorious investment stories.

Got an idea for a story? Email us at [email protected]